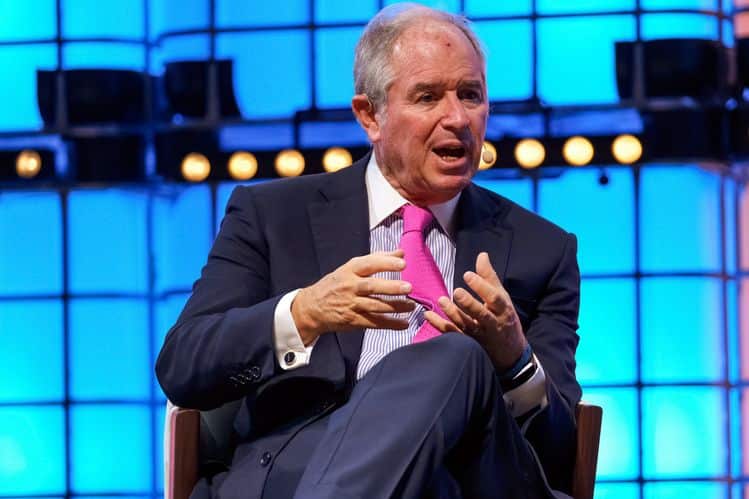

Blackstone chief executive Stephen Schwarzman said exposure to warehouses and apartments supported his mega real estate fund in a trying environment where some rivals lost up to a quarter of their value.

In a Wednesday interview with Barrons Editor-in-Chief David Cho at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Schwarzman said the Blackstone Real Estate Income Trust, known as BREIT, has weathered a higher interest rate environment by avoiding areas of “real tension ” in the real estate market such as offices and shopping centres.

BREIT, which is up about 8% through November, is concentrated in warehouses and apartments, two bets the chief executive says will continue to pay off. But Blackstone had to limit redemptions of the $70 billion flagship retail product in December after withdrawals exceeded its limits.

The boom in online shopping and the move to bring manufacturing capacity back to the United States has benefited warehouses, while apartments have done well as people struggle to enter the housing market, Schwarzman noted. .

Supply of warehouses and apartments is “declining significantly” due to the rising cost of building materials, but demand has remained stable, he adds. This is especially true in the fast-growing Sunbelt region of the United States, which includes Florida and Texas, where BREIT’s assets are heavily exposed, he said.

To protect yourself

Schwarzman said BREIT was able to protect itself from rising rates by fixing around 90% of its debt for 6.5 years. This strategy has helped the product make money as other types of real estate investments have taken a hit, he added.

“Most REITs were down last year by about 20% to 25%. Our cash has increased by 13%… [which was] 50% more than a normal REIT. »

Analysts have speculated on a slew of possible economic outcomes for 2023. The term polycrisis has come up more than once this week at the WEF.

Schwarzman is relatively optimistic about the economic outlook. He says the economy of the developed world is doing better than expected due to the huge amount of savings that households have amassed during the pandemic. In the United States, that figure is around $2.5 billion.

“When the pandemic ended, people were very grateful that they were still here and not damaged in any way and they started spending to celebrate. And they still spend to celebrate,” says Schwarzman.

“What is surprising is that [the Fed’s interest-rate hikes] didn’t have an impact any faster,” he says.

Full pressure

While interest-rate-sensitive industries have felt the pinch of the Federal Reserve’s quantitative tightening, a real squeeze hasn’t happened, Schwarzman says. The CEO pointed to housing starts, which were down about 19%. In a typical recession, they would be down about 35%, he noted.

“The Fed keeps saying they’re going to keep rates high for a long time. I think the reason they do that is they want to see what happens when consumers run out of money special savings,” Schwarzman said. “So I think you’ll have a drop when the full force of higher rates hits the economy.”

Asked about his future career, Schwarzman says he has no intention of slowing down. Between his day job, philanthropy, political work and spending time with his grandchildren, he says he’s never been busier.

“People ask me, ‘Are you planning to retire?’ I say, ‘Who would give up all that?’ »

This article was first published by Barron’s, another Dow Jones Group title

To contact the author of this story with comments or news, email Kristen McGachey